Building Yendor

Why build a guitar?

As a sixteen year old schoolboy I had an interest in music

and had started to learn to play guitar. It was hard going with a cheap acoustic

guitar. I had tried a friends electric guitar, and found it much easier to play.

My family couldn't afford one. Then my headmaster stepped in. He decided that

the boys in the sixth form would not spend the next two years with their heads

in books. He resolved to make us do something practical and marched us over to

the technical wing. Here the woodwork and metalwork teachers were tasked with

getting each of us to do a practical project. We all started something, but

within a month everybody except me had dropped out. My project carried on for

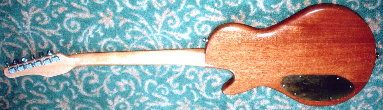

two years in parallel with my A level studies. The result is the guitar you see

here.

The design

Specification

| Scale |

24 3/4 inch (Gibson) |

| Frets |

21 |

| Pick ups |

Di-Marzio Dual sound |

| Length |

42 inches |

| Width |

13 1/2 inches |

The starting point was an article in a woodworking magazine

for a simple "flying V" type guitar with a plywood body and a bolt on neck. Not

very good really. The only thing I used from this was the overall neck

dimensions and fret positions. This was 20 years ago, before the advent of the

WWW, so I had little other information. I studied as many guitars as I could and

perused catalogues in detail.

I based the body shape loosely on the Gibson Les Paul. The

headstock owes more than a nod to the Fender Telecaster. I wanted a through-neck

rather than a bolt-on, both for aesthetic and sustain reasons. The all over

natural wood look is to my eyes very smart, so I avoided having a scratch plate.

I did not particularly want a tremelo arm. I thought this would add un-necessary

complication, so I went with a Gibson style tune-o-matic bridge and tailpiece.

As I wanted a natural wood finish, the colour was dictated by the available

materials in the school workshop.

Construction

Work started with the neck. This was shaped from a single

piece of beech, kindly donated by a friend's father. This was the key component

in the guitar. The overall shape was marked out in pencil, based on the

dimensions from the woodwork magazine article. Rough cutting out was done on the

school bench saw. The next stage involved hours of laborious work with a spoke

shave, rasp and sandpaper to get the neck profile right.

The fret board was a piece of rosewood from school stock

glued to the neck and planed flat. Curvature was then introduced using sandpaper

wrapped around a block. Fret positions were carefully marked, then cut with a

fine razor saw.

Before the frets were fitted the position markers were added.

These are lengths of plastic, cut from a large knitting needle and glued into

holes drilled in the neck. When planed flat their origin is concealed.

Frets are made from commercially available fret wire, cut to

just over length then forced into the approporiate saw cut in the fret board

with a light hammer and a block of wood. When in place the frets must be filed

and sanded with wet and dry paper until smooth and level.

The machine heads and nut were fitted next. I used fairly good quality Schaller

machine heads. The nut is held in place by string tension. Two additional string

trees were added to hold the thinner strings close to the headstock and ensure

sufficient string pressure over the nut. With the addition of the bridge and

tailpiece I could actually string the guitar. At this point I had a

playable guitar, even though it had no body and wasn't very loud! The

final job on the neck was to mark out and cut out the holes for two hum-bucker

pick ups.

The machine heads and nut were fitted next. I used fairly good quality Schaller

machine heads. The nut is held in place by string tension. Two additional string

trees were added to hold the thinner strings close to the headstock and ensure

sufficient string pressure over the nut. With the addition of the bridge and

tailpiece I could actually string the guitar. At this point I had a

playable guitar, even though it had no body and wasn't very loud! The

final job on the neck was to mark out and cut out the holes for two hum-bucker

pick ups.

The body is seeing it's second lease of life as a musical

instrument, being made from a school piano! Before you get visions of Les Paul

shaped holes in the side of the upright at assembly, I must emphasise that the

piano had long since been de-commissioned and stripped for useful material by

the woodwork teacher.

The body is a laminate of two pieces of mahogany to give the necessary

thickness. The two were cut out at the same time on a band saw. The "top" piece

then had the rectangular recess for the neck cut out carefully. The neck is

actually thicker than half of the body, so the "bottom" piece was recessed to

take the rest of the neck. This was done by careful work with a hammer and

chisel, checking the fit regularly. I didn't have access to a router, this being

a very exotic tool in the seventies!

The body is a laminate of two pieces of mahogany to give the necessary

thickness. The two were cut out at the same time on a band saw. The "top" piece

then had the rectangular recess for the neck cut out carefully. The neck is

actually thicker than half of the body, so the "bottom" piece was recessed to

take the rest of the neck. This was done by careful work with a hammer and

chisel, checking the fit regularly. I didn't have access to a router, this being

a very exotic tool in the seventies!

The "bottom" piece had an oval hole cut into it, which would

form the recess for the electrics. This only gave a cavity half the depth of the

body. I needed to achieve a wood thickness of only about 1/8 inch where the

controls poked through the body. This was achieved by drilling small pilot holes

from the front of the guitar where the controls (pots, switches) needed to be. I

then turned the wood over and, using the pilot holes as a guide, drilled most of

the way through the wood with a new sharp wide wood bit. This was done on a

bench drill so that the depth of drill could be safely controlled using the

drills adjustable stops.

The neck and both halves of the body were glued with Resin W

and firmly clamped together over a weekend. Then followed another long session

with the files, rasp and sand paper to shape the body so that it felt

comfortable when held or worn. A key feature which took shape at this time was

the smooth joint between the back of the neck and the body.

Finishing

I now had a complete and working guitar, but it is in bare

wood. Time to take it apart. Everything has to come off. All the fittings, pick

ups, machine heads, knobs, etc.

At first I tried a "Ronseal" type domestic varnish to protect the wood, but I

found that such varnishes are not hard enough for this application. I discovered

this the hard way and had to laboriously sand away all traces of the varnish.

The desired quality of finish was actually achieved by using a two part lacquer.

This comes with a hardener. When the two are mixed a chemical reaction starts

which culminates in a very hard surface, which can be polished to a mirror

finish.

At first I tried a "Ronseal" type domestic varnish to protect the wood, but I

found that such varnishes are not hard enough for this application. I discovered

this the hard way and had to laboriously sand away all traces of the varnish.

The desired quality of finish was actually achieved by using a two part lacquer.

This comes with a hardener. When the two are mixed a chemical reaction starts

which culminates in a very hard surface, which can be polished to a mirror

finish.

Prior to starting to apply the lacquer it is important to get

the wood as smooth as possible. A trick here is to wet the wood to raise the

grain, then sand it down while still wet.

The key to obtaining a good finish is to apply multiple coats

of lacquer and sand down with wet & dry paper between each coat. There is no

short cut.

Most guitars carry the makers name, mine is no exception.

Lettraset was used to apply the legend Yendor Mk 1 on the head

stock (read it backwards). This was done about half way through the lacquer

coats, so that it benefited from the lacquer protection.

Final finishing is achieved by smoothing the lacquer with a

fine liquid abrasive, such as T-cut, then polishing with furniture polish.

Post Script

The finished guitar is pleasing on the eye, plays reasonably

well, and has an acceptable tone. It is certainly much better than anything I

could have affoded to buy at the time. However, with the benefit of hindsight,

if I was doing it again I would pay attention to the following points.

- Woods

The body is good, being made of musical intrument grade mahogany. The neck

however would have benefited from something like Maple.

- Body thickness

The body is made of two layers. A third layer would have given it extra mass

and probably improved the tone and feel.

- Bridge position

I positioned the bridge too close to the fret board. At the time I did not

appreciate the behaviour of stopped strings. Consequently there is

insufficient backwards adjustment to be able to get the intonation quite

right.

- Truss rod

The neck does not incorporate a truss rod. Consequently I cannot adjust the

action to be as low as I would have liked.

Copyright © 2007 Wired Wood.

All rights reserved.

Revised: April, 2008.

|  Wired Wood

Guitars

Wired Wood

Guitars